Welcome to the Practice Guidelines for Treating Gambling Related Problems: An Evidence-based Treatment Guide for Clinicians. We designed this website for treatment professionals who want to learn more about evidence-based treatment approaches for clients experiencing gambling-related problems.

Why use evidence-based guidelines?

Evidence-based practice guidelines help treatment providers deliver scientifically supported clinical services that are best suited to patient needs. Scientific support for treatment strategies is essential to ensuring that treatment services are safe and effective. In short, evidence-based practice guidelines can help providers deliver the best treatments based upon the best evidence for each patient.

These guidelines are for treatment providers who are involved with clients/patients who are struggling with gambling-related health problems or Gambling Disorder. Whether you are a psychologist, a family practitioner, a social worker, or some other type of health service provider, if you have patients who might be affected by gambling, these guidelines are for you.

Evidence-Based Practice in Context: The EBP Triad

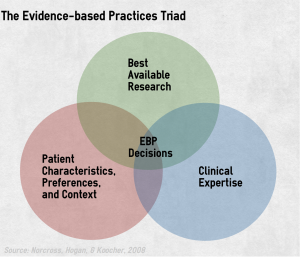

The Institute of Medicine defines evidence-based care as “the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values.” In other words, the research evidence we present in this resource is just one pillar of evidence-based care. Clinicians should begin with research and then integrate their own expertise and their individual patients’ characteristics, culture, and preferences.

In an ideal situation, these three pillars will converge. However, individual patients might require unique decisions and interventions not addressed within the existing literature base.

The EBP Triad requires that patients be actively involved in assessment, case formulation, prevention, therapeutic relationship, treatment, and consultation. [Source: Norcross, Hogan, Koocher, & Maggio, 2017]

What is gambling?

Although most people have gambled at some point during their lifetime, many are unclear about the definition of gambling. Gambling is risking something valuable on an event that is determined at least in part by chance. The gambler hopes that he or she will ‘win,’ and gain something of value. Once placed, a bet cannot be taken back.

When most people think of gambling, they think of slot machines and casinos. But, it’s important to understand that playing bingo, buying lottery or scratch tickets, even betting on office pools — all of these, and many other activities, are forms of gambling.

What is Gambling Disorder?

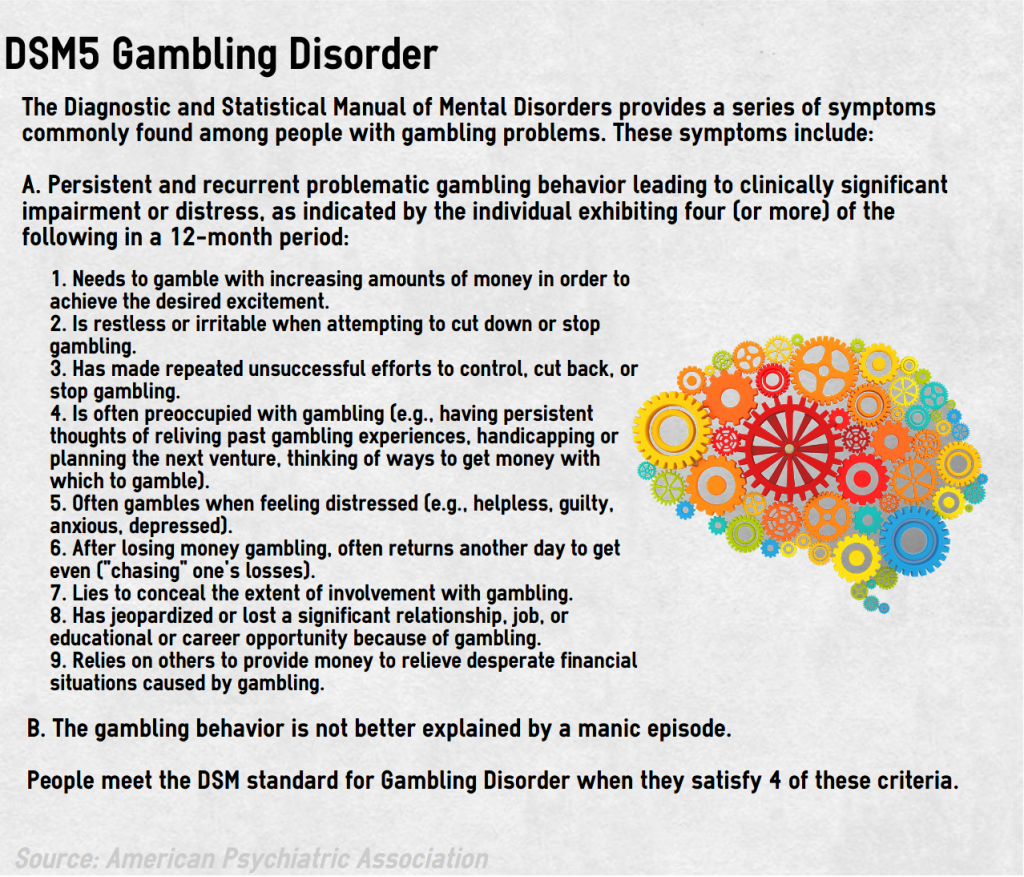

Gambling Disorder is the diagnostic label that the American Psychiatric Association uses to describe clinical levels of excessive gambling in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Most people who struggle with gambling do not have Gambling Disorder, but nonetheless still can experience meaningful harm. Excessive gambling also has been described as gambling-related problems, problem gambling, intemperate gambling, compulsive gambling, and more. These guidelines refer to both Gambling Disorder, and more generally, gambling-related problems.

Gambling Disorder is the diagnostic label that the American Psychiatric Association uses to describe clinical levels of excessive gambling in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Most people who struggle with gambling do not have Gambling Disorder, but nonetheless still can experience meaningful harm. Excessive gambling also has been described as gambling-related problems, problem gambling, intemperate gambling, compulsive gambling, and more. These guidelines refer to both Gambling Disorder, and more generally, gambling-related problems.

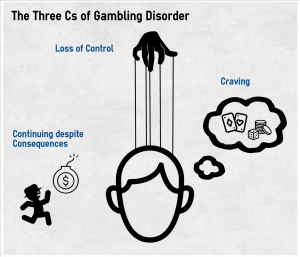

We can sum up the hallmarks of Gambling Disorder using three C’s:

People with Gambling Disorder often feel a loss of Control over their gambling. They might try to quit unsuccessfully or hide their gambling behavior.

People with Gambling Disorder often Continue gambling despite bad consequences. For example, they might not fulfill work or home obligations, or have legal problems. They also might have repeated social problems, like getting into fights and conflicts with other people.

People with Gambling Disorder frequently are preoccupied with gambling. They might Crave gambling or feel a compulsion to gamble.

Who has Gambling Disorder?

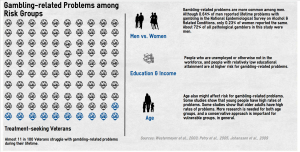

Anyone can develop gambling-related problems. National estimates of gambling-related problems suggest that on average, out of every 100 people you meet, as many as three could have problems with their gambling behavior. Of this group, one person might have Gambling Disorder. [Sources: Petry, Stinson, & Grant, 2005; Kessler et al., 2008]

Anyone can develop gambling-related problems. National estimates of gambling-related problems suggest that on average, out of every 100 people you meet, as many as three could have problems with their gambling behavior. Of this group, one person might have Gambling Disorder. [Sources: Petry, Stinson, & Grant, 2005; Kessler et al., 2008]

Studies show that gambling behavior also is a marker of risk. People who report that they play many different types of games (e.g., slot machines, lotteries, horse racing) are at greater risk for gambling-related problems than people who report that they play few types of games. [LaPlante et al., 2011]

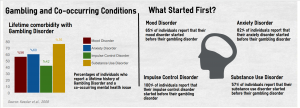

The National Comorbidity Survey – Replication determined that more than 95% of those who report a lifetime history of Gambling Disorder also report a lifetime history of another mental health disorder. About 22% of these people report a single additional disorder, 10% report 2 additional disorders, and 64% report 3 or more additional lifetime disorders. [Source: Kessler et al., 2008]

The National Comorbidity Survey – Replication determined that more than 95% of those who report a lifetime history of Gambling Disorder also report a lifetime history of another mental health disorder. About 22% of these people report a single additional disorder, 10% report 2 additional disorders, and 64% report 3 or more additional lifetime disorders. [Source: Kessler et al., 2008]

Core Elements

Delivering effective treatment is a complex task. Treating addictive behavior involves many different components and must account for the multiple and diverse needs of individual patients. However, there are core activities that are fundamental components of comprehensive addiction treatment. [Source: Leshner, 1999]

Delivering effective treatment is a complex task. Treating addictive behavior involves many different components and must account for the multiple and diverse needs of individual patients. However, there are core activities that are fundamental components of comprehensive addiction treatment. [Source: Leshner, 1999]

Non-specific treatment effects

In the search for the most effective and specific treatment practices, it is essential to remember that non-specific or common factors account for a considerable amount of treatment outcome. Non-specific factors include: (1) the extra-therapeutic attributes that clients bring with them to treatment (e.g., education, family support); (2) relationship factors displayed by the treatment provider (e.g., empathy, caring, warmth); and (3) the hope, expectancies and placebo effects that often associate with the start of treatment. Clinicians should cultivate their non-specific treatment skills. Integrating non-specific treatment skills with gambling-specific treatment strategies holds the potential to maximize treatment benefits. [Source: Hubble, Duncan, & Miller, 1999]

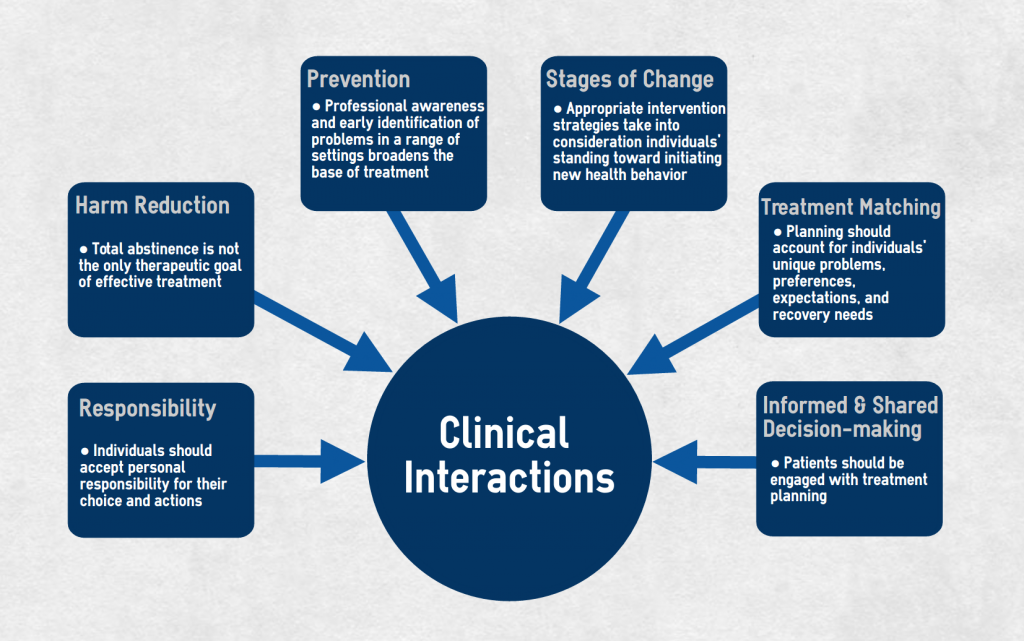

Guiding Principles for Clinical Interactions

Figure: Six primary principles should guide clinical interventions for gambling-related problems.

Treatment Emergencies

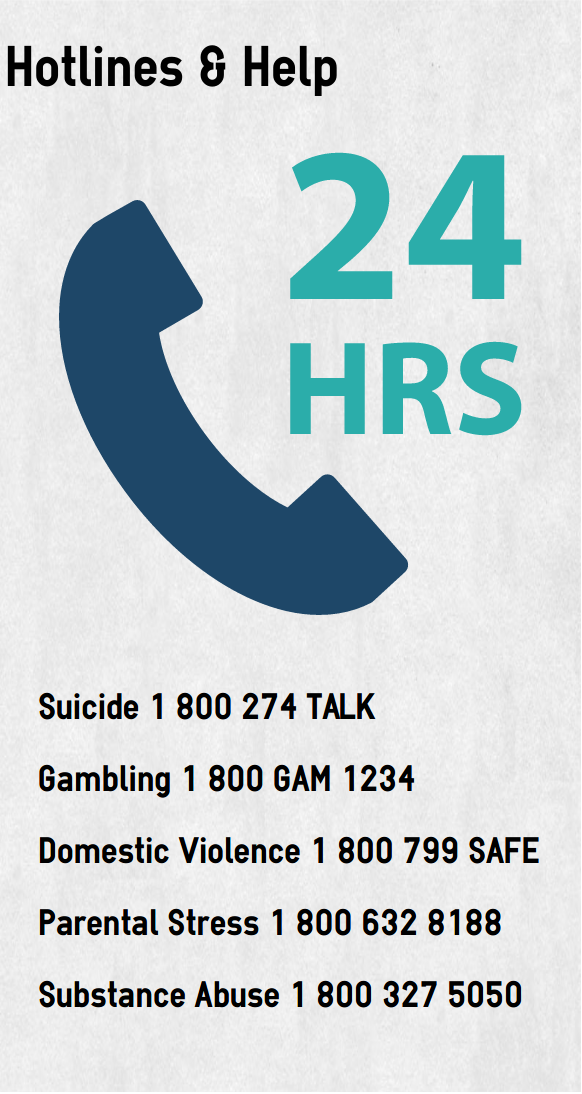

It is difficult to establish a causal link between suicidal thoughts and behaviors and gambling-related problems. However, a number of studies have reported high rates of these issues among people with gambling-related problems. As with treating any disorder that might be associated with suicidal activity, it is important to remain vigilant. Threats of suicide can arise when losses lead to intense feelings of hopelessness, desperation, and conflict or when other conditions such as substance abuse, depression, or major mental illness coexist.

Clinicians who suspect that a client might be experiencing suicidal thoughts or planning should complete an urgent evaluation, followed by prompt treatment or referral, if required.

Discredited Therapies

These guidelines show that evidence-based practice for gambling-related problems is an achievable goal. Unfortunately, the mental health treatment world includes many treatment approaches of questionable origins and efficacy. From crystals, to past lives, to aromatherapy, to facilitated communication – with an evidence-based perspective, it is easy to avoid such discredited treatments. In fact, some have suggested that it might be easier to know what doesn’t work than it is to rigorously determine what does work. [Source: Norcross, Koocher, & Garofalo, 2006, p. 515]

Sticking with evidence-based practices helps health providers avoid unintended consequences and chasing temporary improvements that only are the result of short-term placebo effects. Delphi Panel Experts’ Top Rating of Discredited Treatments for Mental/Behavioral Disorders provides an excellent resource ineffective problem gambling treatment methods.

Sticking with evidence-based practices helps health providers avoid unintended consequences and chasing temporary improvements that only are the result of short-term placebo effects. Delphi Panel Experts’ Top Rating of Discredited Treatments for Mental/Behavioral Disorders provides an excellent resource ineffective problem gambling treatment methods.

Special Populations

Evidence-based Guidelines make it easy to assume that all treatments are equally efficacious for all types of people. However, research in other areas suggests that it might be important to pick treatment approaches with consideration for individuating factors.

Among the many special populations that providers should account for are youth, older adults, women, Aboriginal/First Nation/Indian People, Ethno cultural minorities, the homeless, and those with psychiatric comorbidity. As the EBP Trinity illustrates, careful treatment planning that takes into account individuals’ unique backgrounds and circumstances is important to obtaining agreed upon treatment goals.

Treatment for a Gambling Disorder begins at first contact with a clinician.

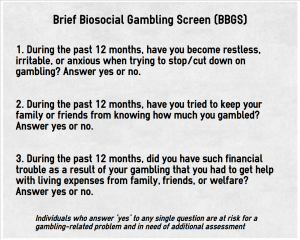

Brief Screening

One of the earliest and best known brief screens for gambling-related problems is the Lie/Bet Scale. This is a two-item screen that asks people to answer (1) Have you ever had to lie to people important to you about how much you gambled? and (2) Have you ever felt the need to bet more and more money? The Lie/Bet Scale has been the subject of a number of psychometric evaluations. Recently, researchers have developed a number of brief screens (i.e., those about 5 items or fewer). You can read summaries about some of these screens on The BASIS.

One of the earliest and best known brief screens for gambling-related problems is the Lie/Bet Scale. This is a two-item screen that asks people to answer (1) Have you ever had to lie to people important to you about how much you gambled? and (2) Have you ever felt the need to bet more and more money? The Lie/Bet Scale has been the subject of a number of psychometric evaluations. Recently, researchers have developed a number of brief screens (i.e., those about 5 items or fewer). You can read summaries about some of these screens on The BASIS.

Learn More from The BASIS:

BBGS vs. NODS-CLIP: Which Brief Screen for Pathological Gambling Wins the Battle of Psychometrics?

Continuing validation of the Brief Biosocial Gambling Screen

Screening for Pathological Gambling: A 2-Question Test

You can access the research behind these screens from these sources:

The Brief Biosocial Gambling Screen

Gebauer, L., LaBrie, R. A., & Shaffer, H. J. (2010). Optimizing DSM-IV-TR classification accuracy: A brief biosocial screen for detecting current gambling disorders among gamblers in the general household population. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(2), 82-90.

Johnson, E. E., Hammer, R., Nora, R. M., Tan, B., Eistenstein, N., & Englehart, C. (1997). The lie/bet questionnaire for screening pathological gamblers. Psychological Reports, 80, 83-88.

Rockloff, M. J. (2012). Validation of the Consumption Screen for Problem Gambling (CSPG). Journal of Gambling Studies, 28(2), 207-216.

Temcheff, C. E., Paskus, T. S., Potenza, M. N., & Derevensky, J. (2016). Which diagnostic criteria are most useful in discriminating between social gambling and individuals with gambling problems? An examination of DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(3), 957-968.

Toce-Gerstein, M., Gerstein, D. R., & Volberg, R. A. (2009). The NODS-CLiP: A rapid screen for adult pathological and problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(4), 541-555.

Volberg, R. A., Munck, I. M., & Petry, N. M. (2011). A quick and simple screening method for pathological and problem gamblers in addiction programs and practices. The American Journal on Addictions, 20, 220-227.

Assessment

The gambling field is awash with assessment tools. Different assessment tools target different aspects of gambling-related problems. The available assessments have been the subject of a number of psychometric evaluations. Depending upon an individual’s clinical needs and a clinician’s need for specific information, different assessment tools are appropriate.

Some popular assessment tools include:

Canadian Problem Gambling Index (CPGI)

Young, M. M., & Wohl, M. J. (2011). The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: An evaluation of the scale and its accompanying profiler software in a clinical setting. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27(3), 467-485.

The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS)

Lesieur, H. R., & Blume, S. B. (1987). The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(9), 1184-1188.

The South Oaks Gambling Screen-revised Adolescent (SOGS-RA)

Boudreau, B., & Poulin, C. (2007). The South Oaks Gambling Screen-revised Adolescent (SOGS-RA) revisited: A cut-point analysis. Journal of Gambling Studies, 23(3), 299-308.

Massachusetts Gambling Screen (MAGS)

Shaffer, H. J., LaBrie, R., Scanlan, K. M., & Cummings, T. N. (1994). Pathological gambling among adolescents: Massachusetts Gambling Screen (MAGS). Journal of Gambling Studies, 10(4), 339-362.

Diagnosis

The American Psychiatric Association recently made a major change to its treatment of gambling-related problems within its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In prior editions, gambling-related problems were included in the manual’s Impulse Control Disorders section under the diagnosis, Pathological Gambling. Today, gambling-related problems are located with other addictive behavior, like Substance Use Disorders, and use the diagnosis, Gambling Disorder. The co-location of gambling with other addictive behavior reflects the shared preceding conditions, developmental processes, and consequences of these problems. Notably, many of the Evidence-based Practices for Treating Gambling Disorder also are evidence-based practices for other expressions of addiction.

The American Psychiatric Association recently made a major change to its treatment of gambling-related problems within its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In prior editions, gambling-related problems were included in the manual’s Impulse Control Disorders section under the diagnosis, Pathological Gambling. Today, gambling-related problems are located with other addictive behavior, like Substance Use Disorders, and use the diagnosis, Gambling Disorder. The co-location of gambling with other addictive behavior reflects the shared preceding conditions, developmental processes, and consequences of these problems. Notably, many of the Evidence-based Practices for Treating Gambling Disorder also are evidence-based practices for other expressions of addiction.

These Evidence-based Guidelines for Treating Gambling Disorder rest upon a systematic search of scientific evaluations of treatment approaches. Different search and inclusion parameters could lead to different outcomes. As more publications become available, the Guidelines will be updated. To recommend a study for inclusion, please use our suggestion and feedback form.

Making the Cut

The systematic search for gambling treatment evidence included reviewing the following sources:

The systematic search for gambling treatment evidence included reviewing the following sources:

- PsycInfo, American Psychological Association

- PubMed(r), National Institutes of Health

- ProQuest

- MEDLINE(r), National Institutes of Health

- Cochrane Register of RCTs, Cochrane Community

- Google Scholar

These Guidelines only include scientific evaluations relevant to the treatment of gambling-related problems that are published in peer review journals. There is less certainty of methodological quality for publications that are not peer reviewed. These Guidelines are limited to English-language publications. Currently, these Guidelines represent an analysis of 134 peer reviewed publications. We coded these publications for a variety of characteristics, such as treatment type, methodology, treatment outcomes, and more. These publications are available for review.

Categorizing Strength of Evidence & Research Design

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

The most frequently studied treatment type for gambling disorder is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). This type of treatment attempts to change the thoughts and behaviors that are fundamental to maintaining a pattern of behavior (e.g., gambling disorder). The goal of CBT for intemperate gambling is to identify and change “cognitive distortions and errors” that are associated with excessive gambling and its adverse sequelae. For gambling, CBT can include at least four components: (a) correcting cognitive distortions about gambling; (b) developing problem solving skills; (c) teaching social skills; and (d) teaching relapse prevention. There are a number of CBT trials that suggest that it is an effective form of treatment for gambling.

Learn More from The BASIS

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Adolescent Problem Gamblers

Feeling better without losing: Decreasing disordered gambling and improving people’s moods

Preventing Dropouts: Compliance-Improving Interventions

Three different paths to improvement; but, is there a difference?

Motivational Enhancement/Interviewing

Motivational enhancement strategies (e.g., motivational counseling; resistance reduction) are brief therapeutic strategies designed to lower resistance and enhance motivation for change. Motivational enhancement strategies augment pre-existing motivation by improving the therapeutic alliance. Further, by attending to the dynamics of ambivalence, clinicians improve the quality of treatment; treatment providers establish a therapeutic context that resonates with the client’s mixed motivations toward their object of addiction (e.g., gambling). These interventions typically accompany other types of interventions as a supplement; however, clinicians can use motivational enhancement interventions on their own. Studies of motivational enhancement suggest that it yields clinically meaningful changes in gambling behavior and symptom experiences. Studies of a single session of motivational enhancement therapy found benefits associated with this treatment persisted as long as 12 months after the intervention. Studies with longer follow up periods are needed to determine whether such clinical effects extend beyond a year.

Learn More from The BASIS

Brief Treatments for Disordered Gambling: What Works and for How Long?

Do the Effects Hold?: Brief Gambling Treatment – Beyond the 12-Month Follow-up

More or Less the Same: Variations on Brief Gambling Treatment

Guided Self-help Interventions

Self-help interventions for gambling include self-guided activities and information workbooks designed to reduce or eliminate gambling. Sometimes these approaches can be accompanied by planned support from a helpline specialist, clergy, a community health specialist, a therapist, or some other treatment provider. More specifically, guided self-help approaches that have been tested include workbooks accompanied by a brief explanatory or informational phone call related to the intervention, motivational interviewing, and/or motivational enhancement. These studies generally show that individuals who engage in guided self-help tend to do better over time than others who do not engage in self-help, such as those who are in a wait list control group. However, some studies do not fully support this outcome; for example, one study reported that workbooks can help people progress toward abstinence, but did not find any benefit for the addition of an explanatory or informational phone call to workbook self-help. Another study also found limited benefit to guided self-help itself.

Learn More from The BASIS

Broadening our treatment systems: Offering self-directed relapse prevention for gambling problems

Do the Effects Hold?: Brief Gambling Treatment – Beyond the 12-Month Follow-up

Brief Treatments for Disordered Gambling: What Works and for How Long?

Personalized Feedback

Personalized Feedback interventions provide individuals with information that compares their own behavior to similar others for a specific activity. This type of intervention requires individuals to report upon their behavior, such as gambling, drinking, or drugging; then, a professional or an automated system (e.g., computer software) provides a report that indicates whether the individual’s behavior is similar to, or different from, how most people behave. People often view Personalized Feedback approaches as “brief” interventions. These interventions might require, for example, a 60-90-minute discussion of the feedback. Some Personalized Feedback interventions might not include an in-person discussion at all. This kind of feedback relies upon software to provide the comparative report. Studies suggest that Personalized Feedback might help alleviate individuals’ gambling-related symptoms. However, findings for this intervention are mixed. For example, one study showed that Personalized Feedback resulted in gambling-related improvements only when investigators controlled for other mental health symptoms. Another study found that, although feedback was associated with a reduction in days gambled, the addition of comparative information did not provide added benefit. This study examined the website, checkyourgambling.net.

Learn More from The BASIS

Feeling better without losing: Decreasing disordered gambling and improving people’s moods

Relapse Prevention

Relapse prevention and recovery training are treatment components that clinicians design and use to increase a person’s ability to identify and cope with high-risk situations that can precipitate relapse. Gambling risk situations might include environmental settings (e.g., casinos, lottery outlets), intrapersonal discomfort (e.g., anger, depression, boredom, stress), and interpersonal difficulties (e.g., finances, work and family). The Inventory of Gambling Situations is one tool that can help individuals identify circumstances that increase their risk of gambling. Relapse prevention’s goal is to help individuals develop coping methods to deal effectively with those specific high-risk situations without relying on unhealthy and maladaptive gambling behavior. A number of studies have incorporated relapse prevention as a component of their trials. These studies suggest that relapse prevention in combination with other cognitive therapy (e.g., cognitive correction) is associated with clinically favorable outcomes, like reducing time and money spent gambling. Cognitive correction is a technique that seeks to correct individuals’ misconceptions of basic gambling-related concepts (e.g., randomness). Other studies have determined that both individual and group relapse prevention treatment for gambling disorder are superior to a no-treatment control group. Taken together, these findings suggest that relapse prevention is a promising and developing treatment approach for gambling.

Learn More from The BASIS

Biology, Addiction, and Gambling: The Role of Rodent Relapse

Doomed to fail? Predictors of problem gambling relapse

Look, But Don’t Touch: An Investigation Into Cue-Exposure, Response-Prevention Treatment

Relapse Among Problem Gamblers

Brief Advice

Brief treatment can take a number of different forms, including limited motivational enhancement therapy, as we mentioned previously. Brief treatment does not necessarily need to include motivational enhancement, however. These interventions might include a 10 minute conversation or a few counseling sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy, for example, but not protracted clinical involvement. A brief treatment might include a gambling disorder screen, information about harmful consequences of excessive gambling, or simply advice for reducing gambling-related harm. Studies of brief advice suggest that it is associated with clinically significant changes in gambling behavior. Documented benefits of brief advice are apparent as early as six weeks following an intervention and as long as nine months later. Additional studies of brief advice from other sources will help confirm brief advice as an important treatment approach for gambling.

Learn More from The BASIS

How do gamblers use a web-based responsible gambling tool?

Medications

There is no specific FDA-approved pharmacotherapy for the treatment of gambling disorder. Researchers are testing a variety of drugs, and some show promise. To date, there are randomized clinical trials that show favorable outcomes for escitalopram, lithium, nalmefene, topiramate, paroxetine, and naltrexone. However, at this time, no single drug has sufficient support for us to classify it as a treatment with “High Quality Empirical Evidence.” Some of these medication trials are quite preliminary. For example, some randomized clinical trials meet the technical definition of a trial, but include as few as four individuals.

Escitalopram is a medication typically used to treat mood disorders. It is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Lithium is a drug frequently used to treat bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder. It is considered a mood stabilizer. Nalamefene is an opioid antagonist. Most often providers use it to treat alcohol-related disorder. Valproate is an anticonvulsant that typically is used to treat seizures, bipolar disorder, and migraines. Topiramate is a nerve pain medication and anticonvulsant that acts on dopamine pathways and typically is used to treat seizures and migraines. Paroxetine is an SSRI; this medication often is used to treat mood disorders. Finally, naltrexone is an opioid antagonist usually used to treat alcohol and opioid use disorders. Additional research is necessary to study the effects of all these drugs before they are used routinely in a clinical setting for gambling-related problems; however, these early studies are promising, and suggest that some drugs might eventually be useful to treat gambling-related problems.

Learn More from The BASIS

Medicating the Elderly: Pharmacotherapy and Older Gamblers

Nalmefene: Examining a New Treatment for Pathological Gambling

Nalmefene: A Well-Tolerated Opioid Antagonist

To medicate or not to medicate – Drug treatment for Level 3 gambling

Cognitive Therapies

Cognitive therapies seek to help individuals learn to rethink certain matters including those that are intrapersonal and interpersonal. For gambling, this might mean developing a better understanding of randomness, or identifying and correcting erroneous beliefs and perceptions, like the illusion of control often associated with gambling and gambling disorder. Two clinical trials from the same source focusing on cognitive correction with relapse prevention suggested favorable clinical outcomes. Other studies with less rigorous designs (i.e., non-randomized or pre-post comparisons) also suggest that cognitive therapies are worthwhile approaches to the treatment of gambling. We are classifying this popular approach to treatment as “developing” for gambling because we need more studies that focus upon cognitive therapy in isolation from multiple sources. However, this treatment approach is quite promising for gambling disorder.

Learn More from The BASIS

Cognitive Therapy: Changing Your Mind

Reshaping Gambling Beliefs Through Group Therapy

Behavioral Therapies

Behavioral therapy seeks to undo learned associations between a particular stimulus, such as gambling triggers, and an unwanted response, such as feeling an urge to gamble when in the presence of a trigger. One example, exposure therapy seeks to help people eliminate the experience of gambling-related urges in response to actual gambling experiences. Similarly, imaginal desensitization intentionally provokes gambling-related urges using imagery and immediately provides assistance with cognitive restructuring and the presence of incompatible responses (e.g., relaxation). One way of doing this is through the use of audiotaped recordings of gambling scenarios. Despite the popularity of this treatment type, most studies of behavioral therapy for gambling disorder rely upon weak experimental designs that make drawing causal attributions about treatment efficacy difficult. One trial, however, shows that, in combination with relapse prevention, imaginal desensitization can reduce key gambling-related urges effectively.

Learn More from The BASIS

Imaginal Desensitization Treatment for Problem Gamblers

The Use of Electric Shock in Aversion Therapy for Problem Gambling

“Limited Empirical Evidence” is a category for treatment approaches that have been evaluated using relatively weak methods. This might include study designs without randomization or control/comparison groups, or it might include small samples or inadequate follow-up periods. Certain medications have limited empirical evidence for treating gambling disorder. These include bupropion, fluvoxamine, olanzapine, sertraline, nefazodone, memantine, carbamazepine, ecopipam, citalopram, and acamprosate. Other treatments that fall in the “limited empirical evidence” for gambling disorder category are acceptance and commitment therapy, behavioral therapy (e.g., exposure therapy), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (i.e., EMDR), mindfulness, hypnosis, meditation, multifaceted inpatient/outpatient, and deep transcranial magnetic stimulation. By categorizing treatments having “limited empirical evidence” we do not mean to imply that these treatments are not, or will not, be proven useful for treating gambling disorder. However, this classification does reveal that there is currently an absence of rigorous scientific studies of these treatments and their impacts upon gambling behavior and symptoms. To read more about these and other studies, click below to access the full bibliography.

Check Out

|

The Brief Addiction Science Information Source (BASIS) is a free weekly addiction science review. The mission is to minimize the addiction’s harmful effects by providing the general public, treatment providers, policy makers and others with access to addiction research. |

|

Gambling Disorder in Your Practice: Information and Resources is an online Continuing Medical Education course dedicated to increasing providers’ understanding of disordered gambling and its importance to their practice. This course includes information about the epidemiology and clinical features of disordered gambling and will detail options for the primary care provider with regard to screening of and referral for disordered gambling. |

|

Your First Step to Change, 2nd Edition The Division recently published the second print edition of Your First Step to Change. |

|

Change Your Gambling, Change Your Life: Strategies for Managing Your Gambling and Improving Your Finances, Relationships, and Health – This book explains how gambling problems are related to other underlying issues. It offers a series of self-tests to help evaluate the degree of gambling problem and analyze the psychological and social context of the behavior, with specific strategies and approaches for ending the problems. |

|

Futures at Stake: Youth, Gambling, and Society – The widespread legalization of gambling across the U.S. has produced concerns for serious social, economic, and health problems. For the first time in this country, an entire generation of young people has reached adulthood within a context of approval and endorsement of gambling as a source of entertainment and recreation.

|

|

APA Addiction Syndrome Handbook – This two-volume handbook provides a comprehensive review of addiction. Volume 1 focuses on the history of addiction and the expressions of addiction. Volume 2 examines recovery, prevention, and other essential issues commonly associated with addiction.

|

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Hubble, M. L., Duncan, B. L., & Miller, S. D. (1999). The Heart & Soul of Change: What Works in Therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Johanssen, A., Grant, J. E., Kim, S. W., Odlaug, B. L., & Gotestam, K. G. (2009). Risk factors for problematic gambling: A critical literature review. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(1), 67-92.

Kessler, R. C., Hwang, I., LaBrie, R. A., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Winters, K. C., & Shaffer, H. J. (2008). DSM-IV pathological gambling in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine, 38, 1351-1360. doi:10.1017/S0033291708002900

LaBrie, R. A., Peller, A. J., LaPlante, D. A., Bernhard, B., Harper, A., Schrier, T., & Shaffer, H. J. (2012). A brief self-help toolkit intervention for gambling problems: A randomized multi-site trial. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(2), 278-289.

LaPlante, D. A., Nelson, S. E., LaBrie, R. A., & Shaffer, H. J. (2011). Disordered gambling, type of gambling and gambling involvement in the British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2007. European Journal of Public Health, 21(4), 532-537. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckp177

Leshner, A. (1999). Science-based views of drug addiction and its treatment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 282(14), 1314-1316.

Norcross, J. C., Hogan, T. P., & Koocher, G. P. (2008). Clinician’s Guide to Evidence-based Practices: Mental health and the Addictions. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Norcross, J. C., Hogan, T. P., Koocher, G. P., & Maggio, L. A. (2017). Clinician’s Guide to Evidence-based Practices: Behavioral Health and Addictions (Second Ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Norcross, J. C., Koocher, G. P., & Garofalo, A. (2006). Discredited psychological treatments and tests: A Delphi poll. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 37(5), 515-522. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.37.5.515

Petry, N. M., Stinson, F., & Grant, B. F. (2005). Comorbity of DSM-IV pathological gambling and other psychiatric disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 66(5), 564-574.

Westermeyer, J., Canive, J., Thuras, P., Oakes, M., & Spring, M. (2013). Pathological and problem gambling among veterans in clinical care: Prevalence, demography, and clinical correlates. The American Journal on Addictions, 22(3), 218-225. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.12011.x

Training

There are numerous other local, state, national, and international training options for providing Gambling Disorder treatment. Contact the Division on Addiction to learn more.

Stay Informed

Sign up here to receive updates about these Practice Guidelines. This page is dynamic, and will be updated as new peer-reviewed publications are released.

Suggestions and Feedback

We’d like to hear from you. Do you know of a peer-reviewed publication that we can add to these Practice Guidelines? Do you have a question or comment that you would like to pass along? Send them to us!

Acknowledgements

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health supported the development of these Practice Guidelines through a contract (INTF2400HH2500224330) with the Division on Addiction at Cambridge Health Alliance, a Harvard Medical School teaching hospital. The principle authors of these guidelines were Drs. Debi A. LaPlante, Heather, M. Gray, and Howard J. Shaffer. Web design by Ms. Vanessa H. Graham and Mr. John H. Kleschinsky. These guidelines were derived, in part, from: Korn, D.A., & Shaffer, H. J. (2004).